The Origins of Insight Meditation

Lineage, like any family tree, is a web of relationships. Lineage is one of the deep meanings of saṅgha, the spiritual community, reflecting the guidance and realization that flows between teachers, students, and friends on the Path. A lineage is a line of teachers and students, but the energy of the Saṅgha also flows through dreams, visions, stories, places, and texts. It is creative, and reinvents itself as conditions change. The practice we call Insight Meditation (vipassanā) is one of many reinventions in Buddhist history that arose as a result of the teachings coming to new lands, new people, and new cultures.

Modern vipassanā has a lineage of teachers and students that traces back to the early 20th century, when reform-oriented and Western-influenced monks in Burma and Thailand invented new practice forms based in the discourses of the Buddha and responding to changing historical and social processes.

Spirit Rock's founder, Jack Kornfield, along with Sharon Salzberg, Joseph Goldstein, and Jacqueline Schwartz founded Insight Meditation Society (IMS) in Barre, MA in 1976, intentionally bringing in multiple Buddhist lineages in addition to the Burmese practice lineage they all shared.

Read about the founding of IMS and Spirit Rock in Jack's article "This Fantastic, Unfolding Experiment."

Our practice is rooted in the teachings of the Buddha as expressed in the Pāli Canon, and one discourse particularly, the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta (The Foundations of Mindfulness, MN 10), but how we’re practicing it is a modern creation, which like many powerful reformations began as resistance to oppression. On this page we'll explore some of the primary streams of practice and innovation that flowed into the global lineage now called Insight Meditation.

The Legacy of Vipassanā

In Burma (now known as Myanmar) after the 1885 British conquest, a popular movement arose to preserve Buddhism through the colonial occupation. The removal of the Burmese king, traditionally the protector of the Dharma, and an influx of Christian missionaries impelled Burmese monks and lay practitioners to organize to protect the monastic Saṅgha and preserve the Dharma. Two influential monks, Ledi Sayādaw and Mingun Sayādaw, focusing on lay people instead of monastics, started what is now called “The Vipassanā Movement.” These venerable Sayādaws (“respected teacher”) and their students are our Dharma ancestors.

Ledi Sayādaw & the U Ba Khin Method

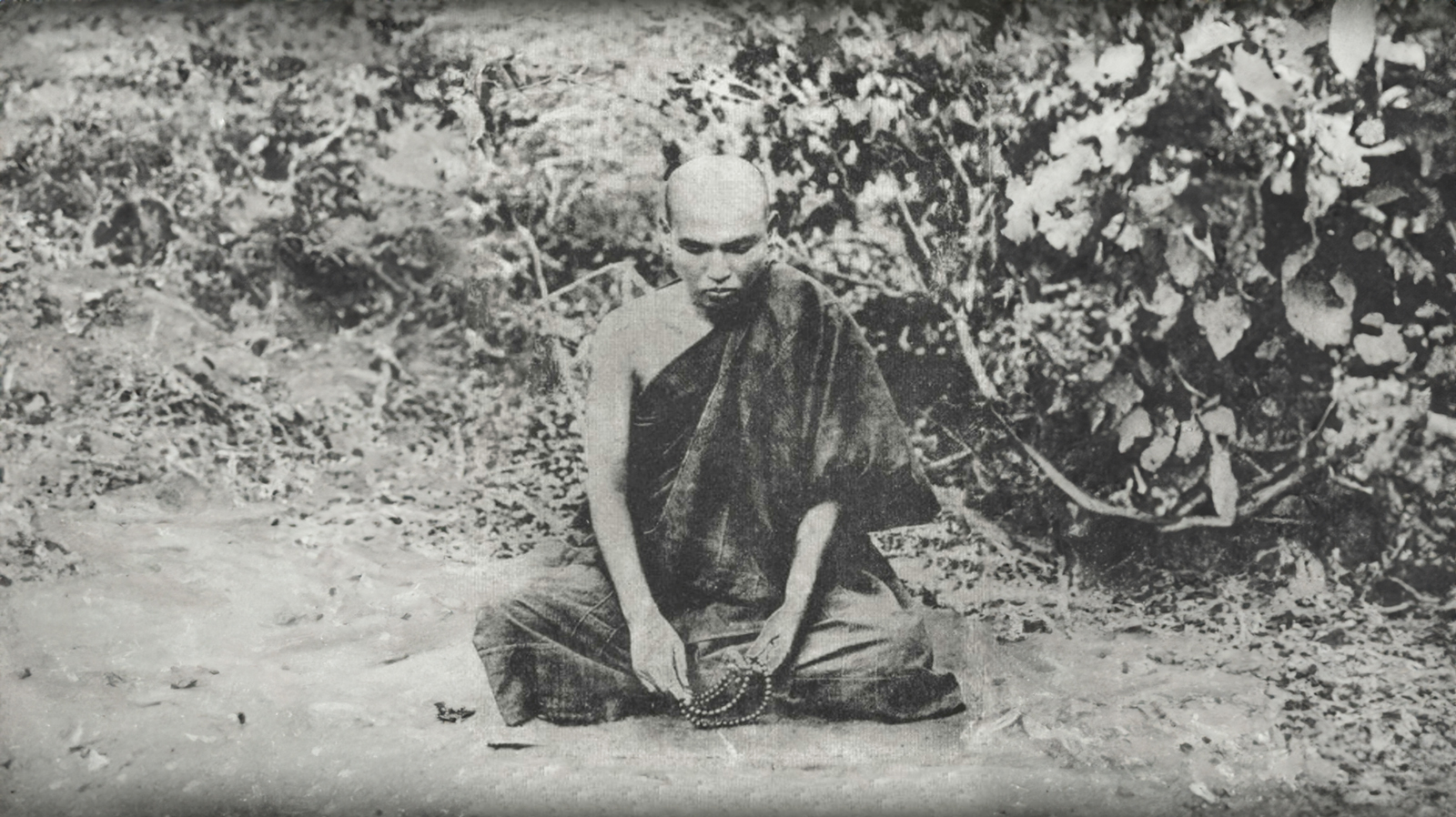

The first Burmese monastic in our modern lineage, Ledi Sayādaw (1846-1923), taught the detailed analytical texts called Abhidhamma to laypeople, and began to revive meditation, which was not commonly practiced in Burma at the time. Ledi developed the idea that anyone could achieve at least the beginning stages of liberation by attending mindfully to ordinary sense perceptions, even without having developed meditative concentration (jhāna). This then-radical idea was the basis for the many different vipassanā styles that would soon develop, some of which would evolve into what we now call mindfulness.

To those whose knowledge is developed, everything within and without oneself, within and without one’s house, within and without one’s village and town, is an object at the sight of which the insight of impermanence may spring up and develop.

— Ledi Sayādaw

The revival of meditation initiated by Ledi Sayādaw continued not through a monastic successor, but through a brilliant lay disciple, Saya Thetgyi (1873-1945), who started the first non-monastic meditation center in Burma. Saya Thetgyi’s student Sayagyi U Ba Khin (1899-1971), a Burmese government accountant, formalized the vipassanā technique of sweeping attention through the body, and U Ba Khin’s Indian student S.N. Goenka popularized the method for a global audience.

Goenka (1924-2013) was a businessman who became devoted to the Dharma, and was asked by U Ba Khin to bring vipassanā practice to India, which he did in 1969, becoming part of the post-independence Buddhist revival in India. There, Goenka became an important teacher for many early Insight Meditation teachers, including Joseph Goldstein and Sharon Salzberg, and subsequently spread U Ba Khin’s method worldwide. Sayagyi U Ba Khin’s most prominent Western student was Ruth Denison (1922-2015), who taught at IMS and Spirit Rock, and founded Dhamma Dena meditation center in Joshua Tree.

Mingun Sayādaw & the Mahāsī Method

The second source for the Vipassanā Movement was Mingun Jetavāna Sayādaw (also known as U Nārada, 1868–1955). As a young monk, he traveled around Burma searching for a teacher who could guide him in meditation, but failed to find one. Following the advice of an elder monk, he turned to the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta. Based on his study of the text, he created his own style of vipassanā focused on continuous mindfulness of changing sensory experiences.

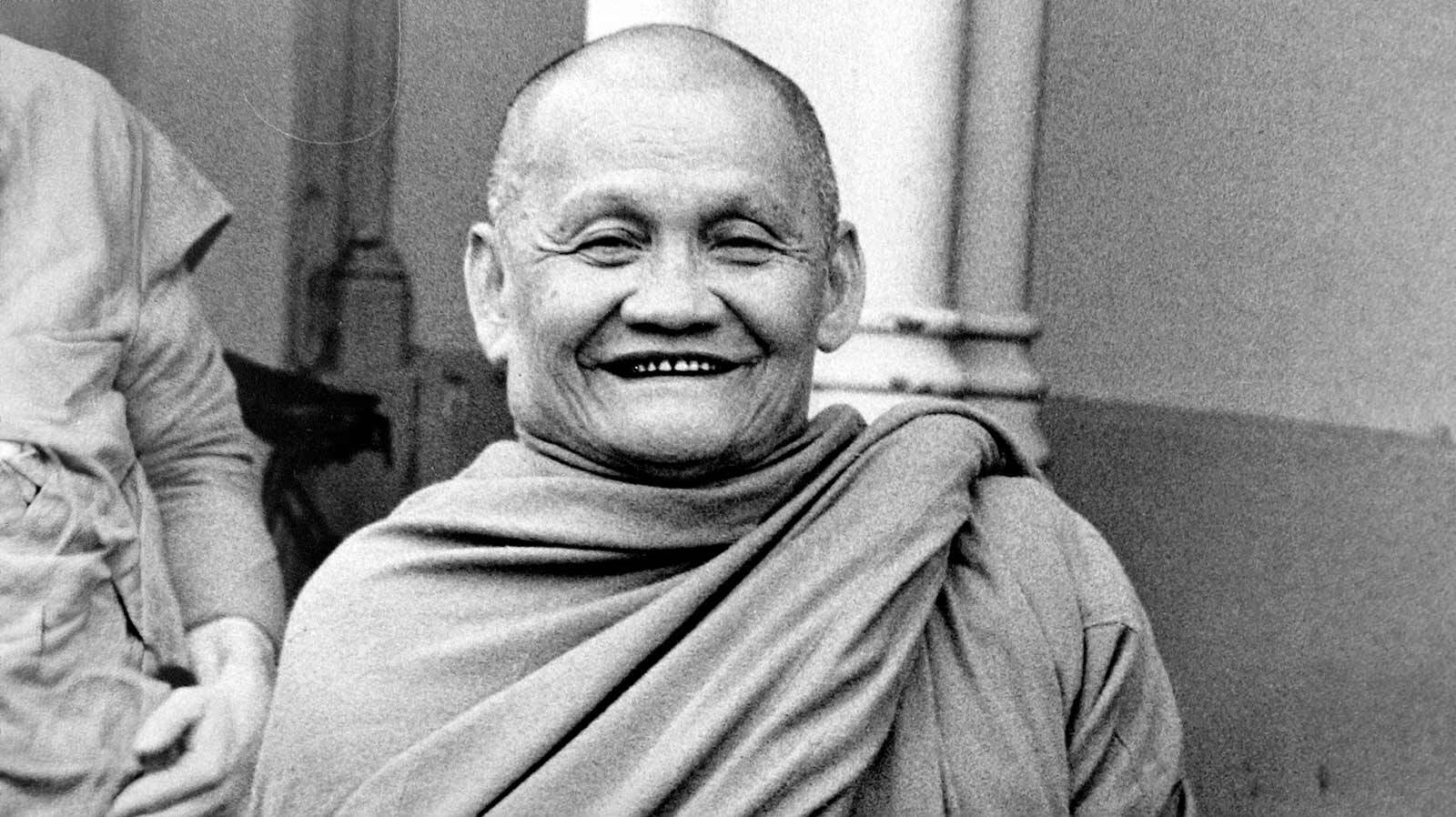

Mingun’s student Mahāsī Sayādaw (1904-1982) developed the technique into what is now called the “Mahāsī method,” which uses continuous mental noting as a support for “momentary concentration” (khaṇika samādhi). Like U Ba Khin’s method, the focus of Mahāsī practice is on experiencing impermanence directly through continuous observation of changing phenomena, without needing to first attain jhāna. This style of practice, which also includes the use of repeated phrases to develop lovingkindness (mettā), is the primary technique the founders of IMS brought back from their study in India and Southeast Asia.

In a historic ceremony at IMS in 1979, Mahāsī Sayādaw gave teaching authorization to four American students: Sharon Salzberg, Joseph Goldstein, Jack Kornfield, and Jacqueline Mandell. Mahāsī’s students U Paṇḍitā (1921-2016) and Anāgarika Munindra (1915-2003), and Munindra’s student Dīpā Mā (1911-1989) all taught at IMS, continuing to develop their teacher’s method, which remains the foundational approach to practice in our lineage.

Recent Burmese teachers to influence Spirit Rock's teachers and practice style include Pa Auk Sayādaw, who teaches a rigorous sequence of deep concentration and directed insight, and Sayādaw U Tejaniya, who emphasizes right view in all activities as the heart of practice.

Practice at IMS and Spirit Rock has evolved from its roots in Burmese vipassanā, and at Spirit Rock is particularly influenced by the Thai Forest Saṅgha style of Ajahn Chah, Jack Kornfield’s root teacher, in the lineage of Ajahn Mun. But the influence of the Burmese Vipassanā movement can still be felt, woven throughout the basic instructions we give, in our use of the Four Foundations of Mindfulness as the sequence of practice, and in the retreat form itself.

Explore the Mahāsī Style of Practice

The Legacy of the Forest Saṅgha

While the Burmese vipassanā lineage gave Insight Meditation its name, retreat structure, and primary meditation method, Spirit Rock is equally connected to a second stream of Buddhist practice: the Thai Forest Tradition, also called the Forest Kamaṭṭhāna tradition or Forest Saṅgha. We trace this lineage through our founder Jack Kornfield’s root teacher, the Thai master Ajahn Chah (1918-92; Ajahn means “teacher”) to a renowned wilderness-dwelling monk, Ajahn Mun.

Ajahn Mun & the Kamaṭṭhāna Tradition

Thai Buddhist culture in the 19th century was heavily ritualized, focused on study, precepts, merit making, and outer renunciation, but with few monks (bhikkhu) practicing meditation, and the women’s monastic tradition long lost. Many believed that nibbāna—the end of suffering—was no longer possible. Modern conditions seemed so unsupportive that it was thought to be impossible to achieve the highest levels of tranquility and clarity of heart. But in the early years of the 20th century, a reform movement began that sought to rediscover effective meditation practices and restore the power of monastic life as a skillful path to liberation.

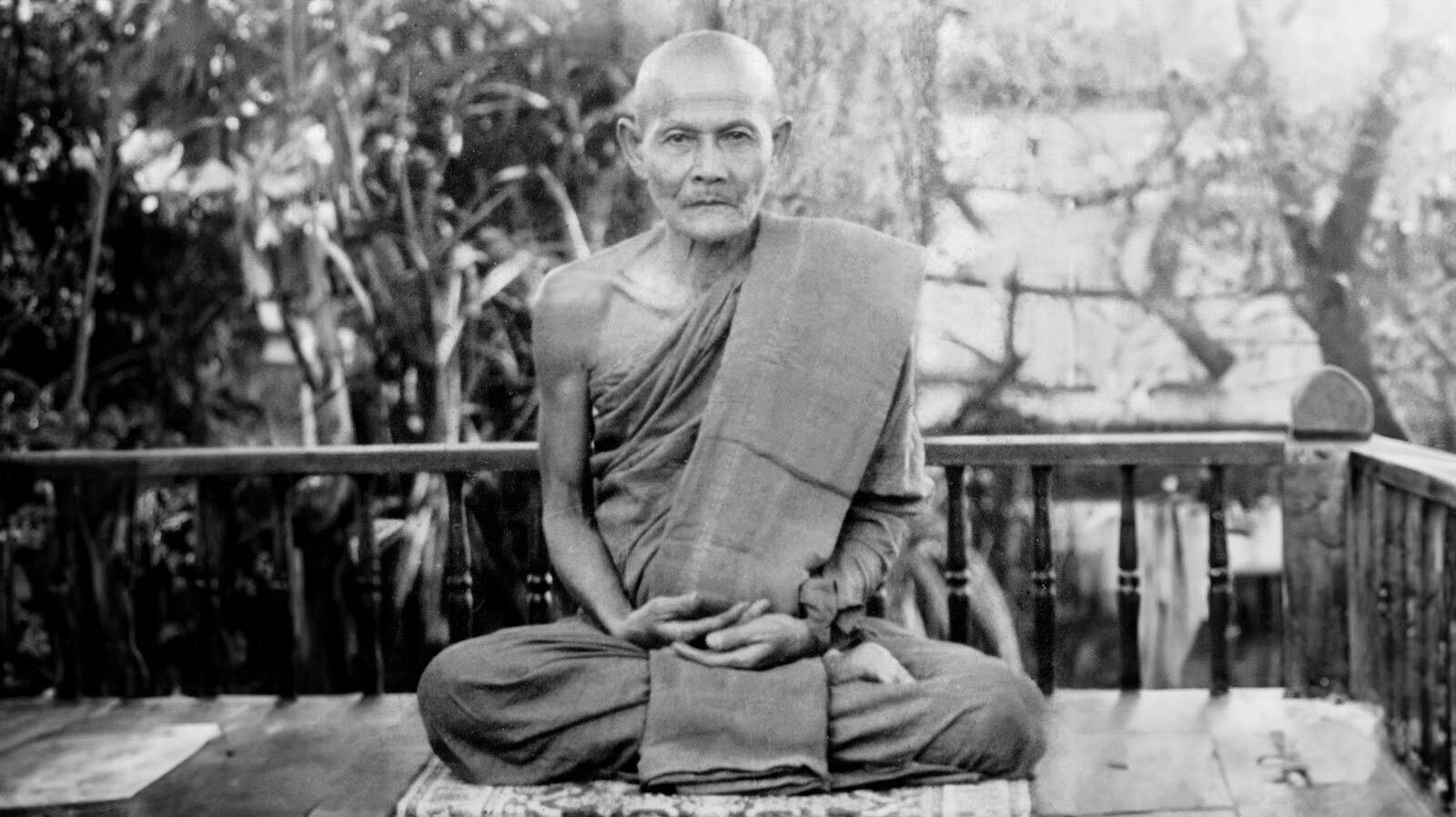

As a young monk, Bhikkhu Mun Bhūridatta (1870-1949) had studied meditation with a teacher named Ajahn Sao, but though the two lived together for many years, Ajahn Sao was unable to give Bhikkhu Mun the precise meditation guidance he sought. Leaving Ajahn Sao and traveling alone in the jungles and forests of northeastern Thailand and Laos, Bhikkhu Mun developed a style of meditation and ascetic life he felt was similar to what the Buddha and the early Saṅgha had practiced, and eventually became a sought-after teacher (ajahn or ācariya), widely considered to have attained liberation and become an arahant, a fully enlightened sage.

Ajahn Mun’s practice centered around living in the wilderness, focusing relentlessly on freeing the heart-mind (citta) from greed, hatred, and delusion. He merged tranquility (samatha) and investigation (vipassanā) into a dynamic inner process, tracking the movement of the mind closely in order to confront unskillful states as they arose. He had a tendency toward visions, and was said to be able to converse with spirits (devas) and animals, teaching them the Dhamma and being protected by them when he practiced in dangerous wild places.

Ajahn Mun’s form of practice came to be known as the Forest Tradition, or Forest Kamaṭṭhāna, meaning “place of practice,” in contrast to the more study and ritual-oriented activities undertaken by urban monks. Though the Forest Tradition and the more mainstream styles were in conflict for many years, respect began to be given to the forest monks when it became clear how strong their practice was.

Ajahn Chah & the Forest Saṅgha

Near the end of Ajahn Mun’s life, a young monk named Ajahn Chah studied with him briefly, inspired by his precise observance of vinaya, and the ascetic practices (dhutaṅga) that Ajahn Mun had revived. Ajahn Chah later described Ajahn Mun’s instructions to him:

Do not focus on the experiences of meditation, however beautiful or painful they are. Instead turn back to see who is being aware, become the One Who Knows, the pure awareness.

Although the teachings are indeed extensive, at their heart they are very simple. With mindfulness established, if it is seen that everything arises in the heart-mind, right there is the true path of practice.

(Ajahn Chah)

These simple but profound instructions transformed Ajahn Chah’s practice. This approach became one of the legacies of the Forest Tradition, and you may feel echoes of it in the open, flexible style of mindfulness we practice at Spirit Rock.

Ajahn Chah wandered in solitude for seven years, following the example of his teacher, before settling down in 1954 in a “fever-ridden, haunted” forest near his home town of Pah Pong in the rural province of Ubon. A monastery grew up around him there, called Wat Pah Pong. Carrying the skill and wisdom he had learned surviving in the wild into communal life, Ajahn Chah focused on ordinary activities as the place of practice, and his community grew to be respected for their sincere, rigorous lifestyle.

The Forest Saṅgha in the West

In 1967, an American monk named Sumedho began studying with Ajahn Chah, and by 1969 there were a small number of Western monks practicing at Wat Pah Pong. One of the first was a young Jack Kornfield, fresh out of the Peace Corps.

Over the years as the number of English-speaking monks grew, Ajahn Chah supported them to form a branch monastery nearby, called Wat Pah Nanachat, the “International Forest Monastery.” Ajahn Sumedho was its first abbot. In 1977, Ajahn Chah was invited to England, and in 1979 Ajahn Sumedho became abbot of the first Forest Saṅgha monastery outside of Thailand, called Cittaviveka, in the small Hampshire village of Chithurst. Other centers soon followed, including a larger monastery, Amaravati, branch monasteries elsewhere in the UK and Europe, and in 1995 Abhayagiri opened in Ukiah, the first US branch of the Forest Saṅgha, with Ajahns Amaro and Pasanno as co-abbots.

Ajahn Chah died from diabetes in 1992 after being paralyzed and silent for 10 years. Over a million people, including the Thai royal family, attended the funeral of this beloved teacher whose transmission already spanned the globe.

Other Thai teachers that have been important for the Spirit Rock community include the philosophically and politically-engaged Ajahn Buddhadasa of Wat Suan Mokkh, and Ajahn Lee Dhammadaro, whose lineage of samādhi based in the full-body breath is carried by Ṭhānissaro Bhikkhu of Wat Mettā in San Diego.

The Bhikkhunī Order is Restored

As the western Saṅgha grew, women began to arrive wishing to practice and ordain. The Theravāda women’s monastic lineage, however, had been broken for nearly 1000 years, due to political instability and lack of support. Powerful monks had long maintained that it could not be revived, so the Thai substitute was an order of female renunciates called maechī who kept 8 precepts rather than the full 311 of a fully ordained nun (bhikkhunī). When the Saṅgha put down roots in England, this limited ordination was continued with the first four nuns ordained in 1979, one of whom was Thanissara, now teaching at Spirit Rock. In 1984 the 10-precept sīladharā ordination was established at Cittaviveka.

Throughout the Theravāda world in the 1980s and 90s (as well as in some Tibetan Buddhist traditions), keeping women in inferior and less supported monastic roles was increasingly being challenged. After decades of organizing, a series of historic ordinations took place, most prominently in Bodhgayā, India in 1998, that reestablished the bhikkhunī lineage. The Thai monastic authorities rejected the ordinations as invalid, even as the nuns in the UK monasteries, alongside lay supporters, were pushing back against the lack of autonomy and full recognition for nuns.

In 2009, in response to growing pressure for full bhikkhunī ordination, a small group of senior monks in the UK monasteries of Chithurst and Amaravati enacted legislation, known as the Five Points, that blocked all pathways for nuns in the Ajahn Chah lineage to take full bhikkhunī ordination. While some sīladharā remained, the impact was that most nuns left, including several founding nuns from Chithurst, including Ayyas Ānandabodhī and Santacittā.

Ayya Ānandabodhī and Ayya Santacittā ordained as full bhikkhunīs at a historic ceremony at Spirit Rock on October 17, 2011, and established Āloka Vihāra Forest Monastery in Placerville, CA as a training monastery for bhikkhunīs (now closed). Though the Ajahn Chah tradition is the heart of their practice style, their ordination as bhikkhunīs was conferred by senior bhikkhus from Sri Lankan and Western lineages, with Ayya Tathālokā, the senior Western bhikkhunī, as their preceptor.

Following the Boghgayā bhikkhunī ordinations and others, there are now growing bhikkhunī communities in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Australia, and globally. Spirit Rock is honored to be able to support this historic restoration of a vital part of the Saṅgha. Though there is far to go for the new bhikkhunī communities to be fully accepted, their thousand-year absence is ending, and the women’s monastic order is on the way to being restored.

The Teachings of the Forest Saṅgha

Now international, the Forest Saṅgha preserves the teaching of Ajahn Chah and other important teachers in Ajahn Mun’s lineage. Other important Forest Tradition lineages are represented at Metta Forest Monastery in San Diego, and Wat Pa Baan Taad and Suan Mokkh in Thailand.

The heart of Ajahn Chah’s practice can be heard in his famous teaching, “A Still Forest Pool”:

Try to be mindful and let things take their natural course. Then your mind will become quieter and quieter in any surroundings. It will become still like a clear forest pool. Then all kinds of wonderful and rare animals will come to drink at the pool. You will see clearly the nature of all things (saṅkhārās) in the world. You will see many wonderful and strange things come and go. But you will be still. Problems will arise and you will see through them immediately. This is the happiness of the Buddha.

(Ajahn Chah)

Practicing in this way, we ourselves become what Ajahn Chah calls “the One Who Knows,” an awareness that is open and clear without contracting around any experience. When we bring this kind of presence to all our activities, not grasping at anything whether beautiful or difficult, we find what Ajahn Mun taught Ajahn Chah: “the true path of practice” that leads to the end of suffering.

Forest Saṅgha Teachings at Spirit Rock

Beginning with Ajahn Sumedho and Jack, two of the first Western disciples of Ajahn Chah, reflecting on their beloved teacher, we hear talks and meditations from Ayya (Venerable) Ānandabodhī, Thanissara, Kittisaro, Ajahn Amaro, and Ajahn Pasanno, showing the elegance of approach and deep wisdom of the Forest Saṅgha tradition.

Spirit Rock cherishes our continued connection to the monastic Saṅgha, and encourages all who desire a connection to the roots of Buddhist practice to spend time with, and support, the monastics.